American artist and painter, Edward Hopper, didn’t achieve much recognition in his lifetime. Today, critics laud his work as quintessential “American” in spirit as he developed a distinctive signature style. His personal life was fraught with toil and resentment as he watched his contemporaries rise to fame and fortune. He was a married man who had no children and his wife stood as a pillar of support, augmenting his intellect, emotion and career. He was a shy, quiet, somewhat reclusive artist who was appalled by abstract modernism and its advent in the American art landscape. He was cynical of critics who failed to share his viewpoint that art is an expression of an artist’s emotional conscience.

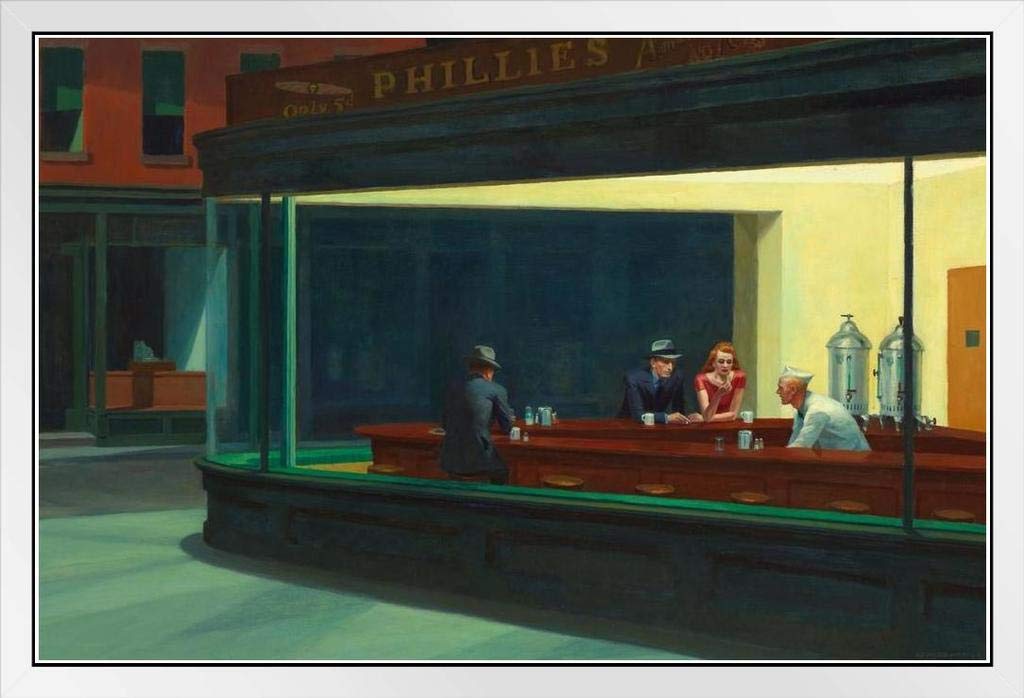

Nighthawks, Ed. Hopper, 1942, Oil on canvas, 33.125 x 60 in.

“Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world … The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm.”

~Edward Hopper

This post is my evaluation and learning of the man and his works.

DEVELOPMENT

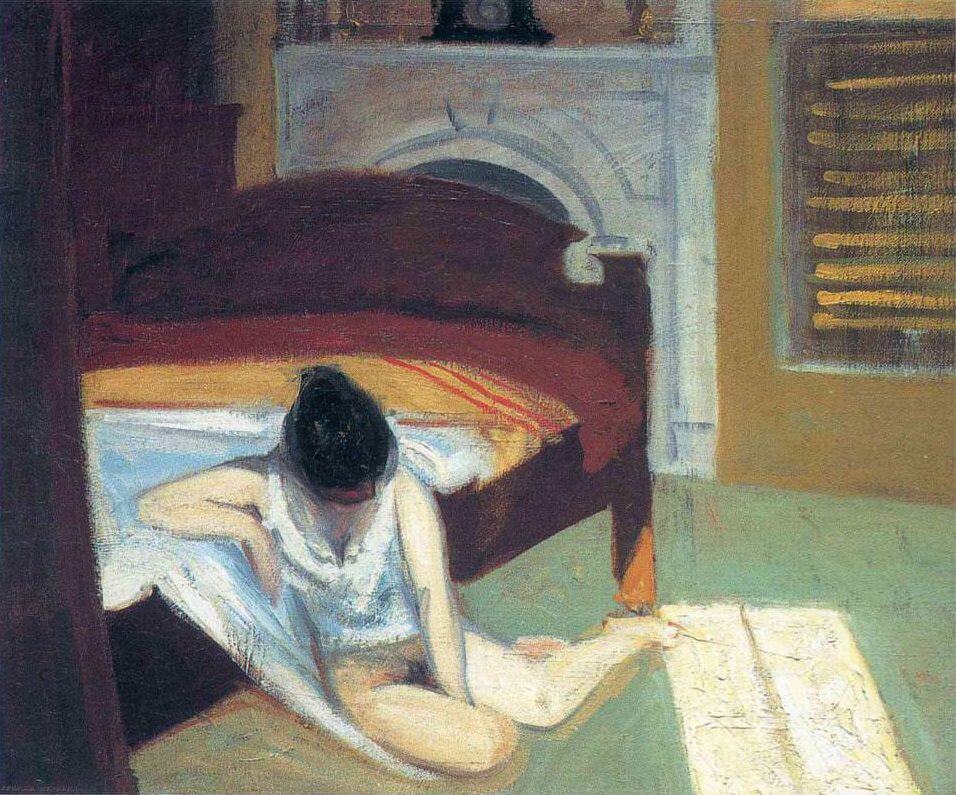

Summer Interior, Ed. Hopper, 1909, Oil on canvas, 24 x 29 in.

Edward Hopper was the second child of Garrett H. Hopper and Elizabeth G. Smith, born in 1882 in Nyack, New York. Belonging to a middle-class household, he showed inclination towards art; a somewhat precocious child, he signed and dated his sketching from the age of ten. He was exceptionally tall, already six feets by his twelfth birthday and his physique isolated him psychologically from his peers through his life.

He read varied writers such as Victor Hugo, Arthur Rimbaud, Thomas Mann, Goethe, Marcel Proust, Emerson, Robert Frost, Henrik Ibsen, Ernst Hemingway avidly from his father’s library whom he remarked as “an incipient intellectual who never quite made it” and was intimately familiar with the writings of Sigmond Freud and Carl Jung.

After graduation from Nyack High School, he studied art at Chase School under the guidance of Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller. He took up a job as an illustrator to support himself but he resented that occupation throughout his life.

He travelled to Europe, visiting England, Holland, Germany and Belgium while staying at Paris in 1906 to 1907. He made two subsequent trips to Europe in 1909 and 1910 and brought with him an admiration for Paris and parisians.

“Paris is a very graceful and beautiful city, almost too formal and sweet to the taste after the raw disorder of New York. Everything seems to have been planned with the purpose of forming a most harmonious whole which certainly has been done.”

FRENCH INFLUENCE AND FINDING AN AMERICAN STYLE

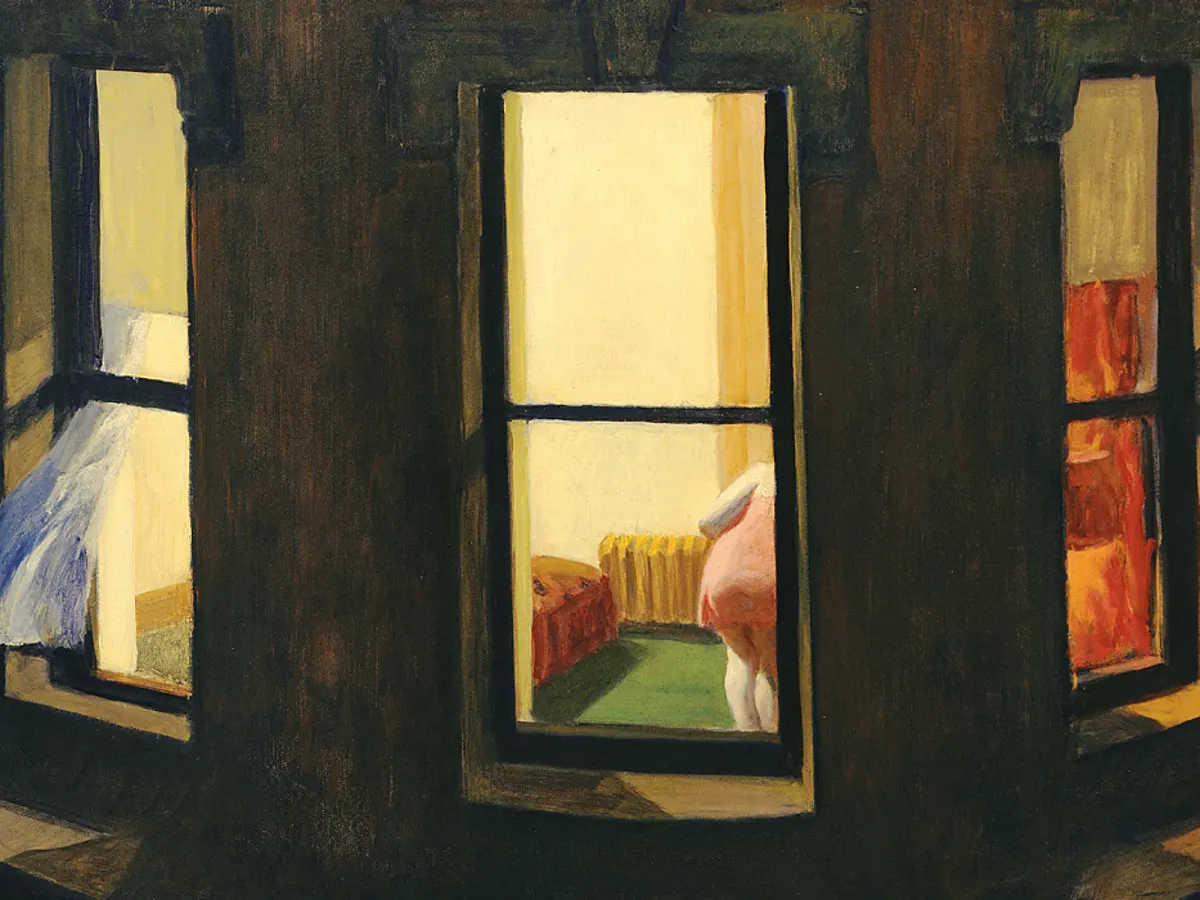

Night Windows, Ed. Hopper, 1928, Oil on canvas, 29 x 34 in.

Hopper appeared at the New York art scene when critics and artists were talking about “cultural nationalism” — a phrase to emphasize a dire need for the artists, dramatists and writers to develop “a home-grown art, out of our own soil”. His early works influenced by French landscapes and philosophies, such as the monumental “Soir Bleu” rose to tepid critical acclaim in a group exhibition in 1915. These encounters made Hopper self-critical and demanding of himself as an artist. Self-doubtful, he grew cynical of critics:

“I don’t know what my identity is. The critics give you an identity. And sometimes, even you give it a push.”

…as for artists, he remarked:

“Ninety per cent of them are forgotten ten minutes after they are dead.”

All this not to form a cold, harsh image of the man. His sense of humor, though submerged, was profound. His youthful caricatures and cartoons hint at his playful side. In one from 1900, all four diners at a boardinghouse request chicked legs – to which the landlady remarked in visible disagreement: “Gentlemen, a chicken is not a quadruped”. His romantic nature is seen in etchings such as “Les Deux Pigeons” (1920) and “Summer Afternoon” (1947).

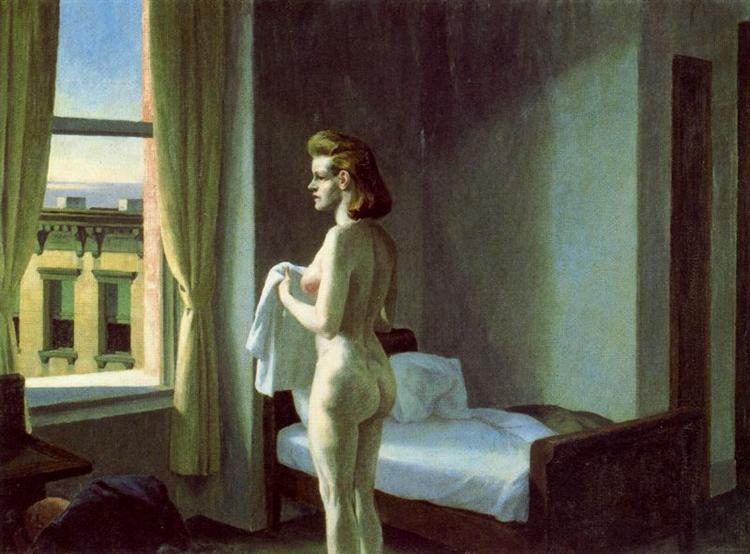

Morning in a City, Ed. Hopper, 1944, Oil on canvas, 44 5/16 x 59 13/16 in.

He only revealed his romance and intellectual sophistication to his wife Josephine Nivison to whom he was married till his death in 1967 for forty-three years. Jo, herself an artist, subjugated her career for her husband and was possessive of him, insisting on being the model for all his female figures.

Hopper insisted on his works being identified as an expression, a projection of his psyche and not a singular cultural pronounciation.

“The American quality is in a painter — he doesn’t have to strive for it”

He associated his art with his inner feelings as highlighted by a quotation by Goethe he carried in his wallet:

“The beginning and end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by means of the world that is in me, all things being grasped, related, retreated, moulded and reconstructed in a personal form and an original manner.”

Office at Night, Ed. Hopper, 1940, Oil on canvas, 22 3/16 x 25 1/8 in.

Now that we have a reasonable introduction to the man, onwards to his enthralling works.

SIGNATURE FEATURES AND ELEMENTS

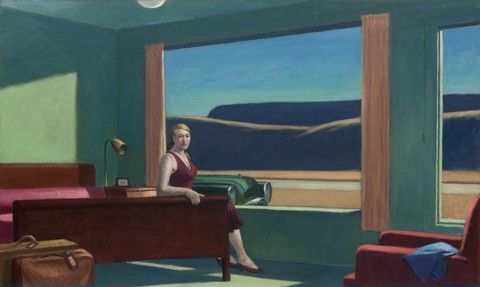

Hopper’s paintings, especially, his city studies, grant us a unique, voyueristic, almost intruder’s perspective to peer into the lives of psychologically solitary figures. Someone on the internet said, “You can sleep inside an Edward Hopper painting”. Rightfully. The serene calmness of his painting, almost eerie tranquility and choice of a handful of figures give his painting a kind of vast metaspace for the viewer to reach in and explore. Take Western Motel, 1957, Oil on canvas, 30.25 x 50.125 inches and People in the Sun, 1960, Oil on canvas, 40 x 60 inches.

Western Motel, Ed. Hopper, 1957, Oil on canvas, 30.25 x 50.125 inches

Sharp perspective, crisp straight lines, vast spaces, huge window, the play of light and shadow and in the center of it, a blonde woman in red staring straight at the viewer. This painting represents almost all elements that came to be known as signature Hopper realism — sometimes carelessly termed “Hopperesque”, in his later work.

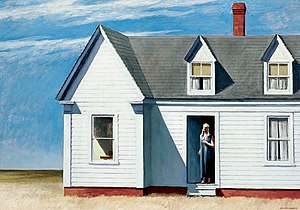

Almost perfect “realist” perspective of objects, slightly utopic; house walls without blemishes or moss outgrowths, roads and streets perfectly paved without a scar or imperfection. High Noon, 1949, Oil on canvas, 28 x 40 inches and Cape Cod Morning, 1950, Oil on canvas, 34 x 40 inches helpfully illustrates these qualities.

High Noon, Ed. Hopper, 1949, Oil on canvas, 28 x 40 in.

Solitary figures

Solitary figures are suspended in a frozen melancholic mood, as if they want to say so much yet they just exist. Direct, fixating gaze is also dramatically observed in Office at night where the secretary is looking at us with her upper body turned as her dress glaringly accentuates her figure. People in his painting are alone, terribly alone and contemplative. Perhaps the most famous of these people would be the lonely man in Nighthawks, donning a navy coat and a hat, with his back turned towards the audience as he sits solemnly at a New York diner late at night. Even in New York Movie, (one of my favourites), a painting of a theater’s interior with many people, he creates a magical portrayal of a sad and aloof lady, hands on her cheek, distant from the pandemonium and chattering of people. We forget about the theater and are somehow drawn towards her inspite of the opulence and happenings. Her mere appearance evokes sympathy in our hearts.

New York Movie, Ed. Hopper, 1939, Oil on canvas, 32.25 x 40.125 in.

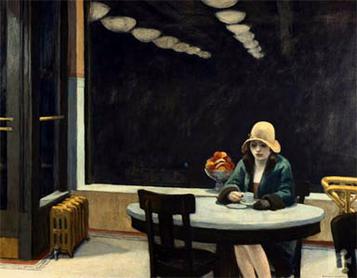

Another of my favourite is Night windows, 1928, Oil on canvas, 29 34 inches, an intimate moment of a lady from a intrusive, almost voyueristic perspective. Further examples may be given of Evening wind, 1924, Etching, 67/8 x 81/4 inches, a nude in bed who is staring out the window as a brisk wind unfurls the curtains or Summer Interior, 1909, another of my favourite, a partial nude with head hung low and deep in thought against the side of her bed. Automat, 1927 (a semi-favourite), Moonlight Interior, 1921-1923 and Girl on Sewing Machine, 1921 are also often cited.

Automat, Ed. Hopper, 1927, Oil on canvas, 28.125 x 36 in.

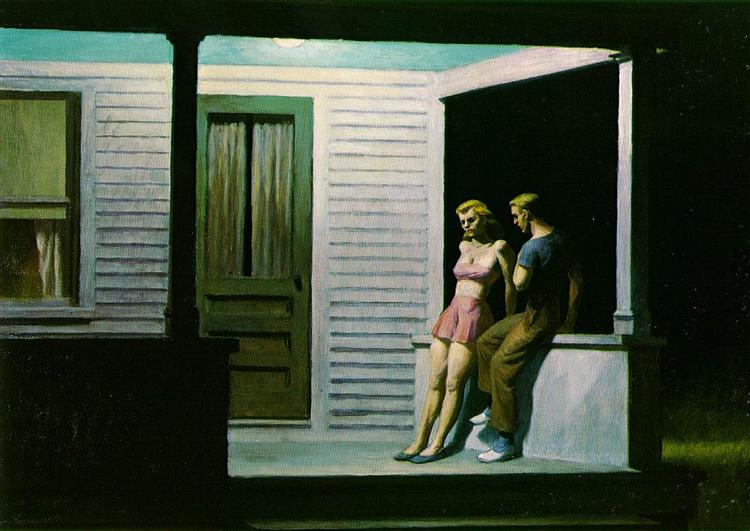

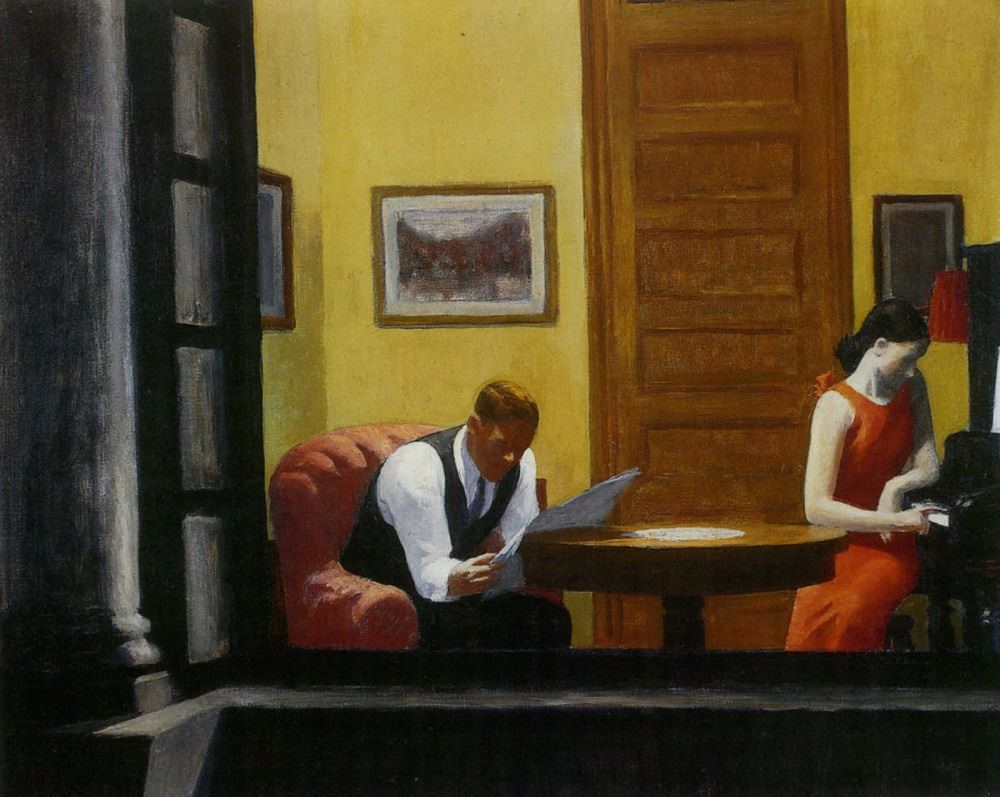

Couples

Couples also feature in Hopper’s imaginative universe, but only as symbolic companions to each other. There is little intimacy or romance depicted. Nobody ever makes contact with anybody else. Hands on head (in distress?), nonchalantly looking out the window seemingly oblivious to the presence of their partner, coolly dozing with the back turned towards others, these couples are representative of Hopper’s personal experiences with romance and intimacy. In Summer Evening, 1947, a young couple, against glaring electric light are seen engrossed in a tussle, physically apart from each other, a conflict between themselves, a conflict within themselves? Their expressions and postures are forlorn and… quiet.

Summer Evening, Ed. Hopper, 1947, Oil on canvas, 30 x 42 in.

Or Room in New York, 1932, Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 in. (my favourite), we catch a young couple in visible agony as they are struggling to fulfill their relationship somehow, the young man intensely reading the newspaper and the lady, a distance apart, head bowed low, mindlessly striking a key at the piano and contemplating her life. The intrusive, almost voyueristic window perspective that we see them through makes us feel like we are prying into the personal affairs of two people but then how many people openly acknowledge they are in a failing marriage?

Room in New York, Ed. Hopper, 1932, Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 in.

More instances can be seen in Cape Cod Evening, 1939, Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches, Second Story Sunlight, Sunlight on Brownstones, 1956, Seawatchers, 1952, Summer in the City, 1949, Excursion into Philosophy, 1959 and Hotel by a railroad, 1952

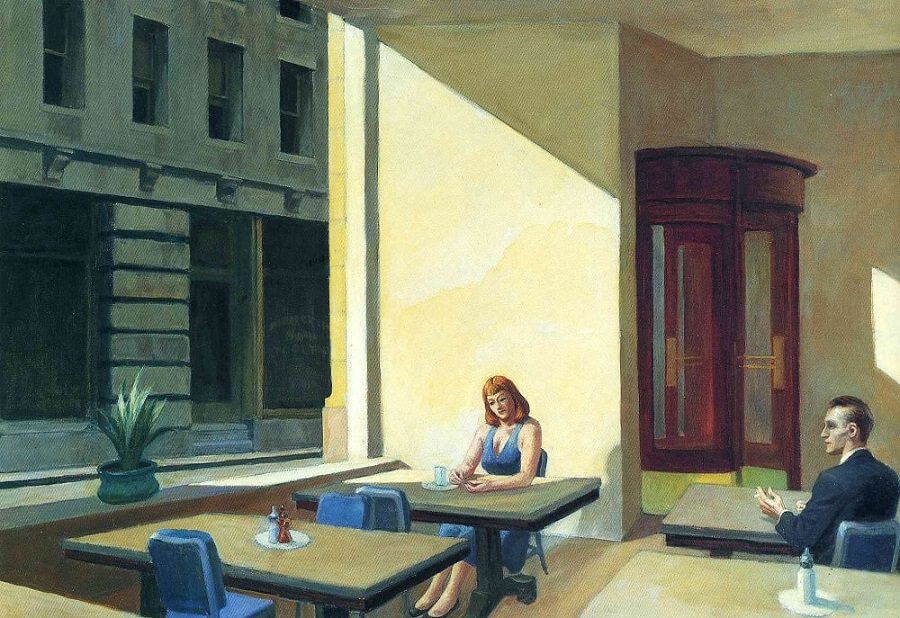

Light and shadows

Figures staring out huge windows at bright, sunlit, almost delectable outside environments. Sunlight in a Cafeteria, Second Story Sunlight, Morning in a City, Morning Sun, Cape Cod Morning, High Noon, A Woman in the Sun.

Sunlight in a Cafeteria, Ed. Hopper, 1958, Oil on canvas, 40 3/16 x 60 1/8 in.

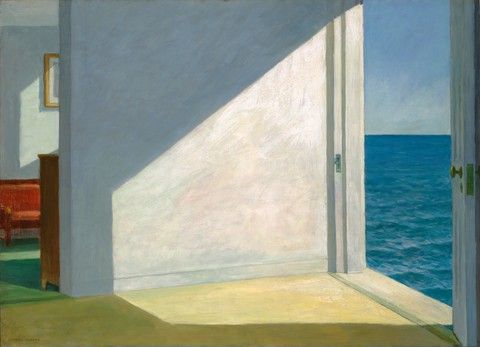

Sunlight

Rooms by the Sea, 1951, Sun in an Empty Room, 1963 and the beautiful Railroad sunset, 1929, Oil on canvas, 35 x 60 inches. I have always loved the sun!

Rooms by the Sea, Ed. Hopper, 1951, Oil on canvas, 29.5 x 40 in.

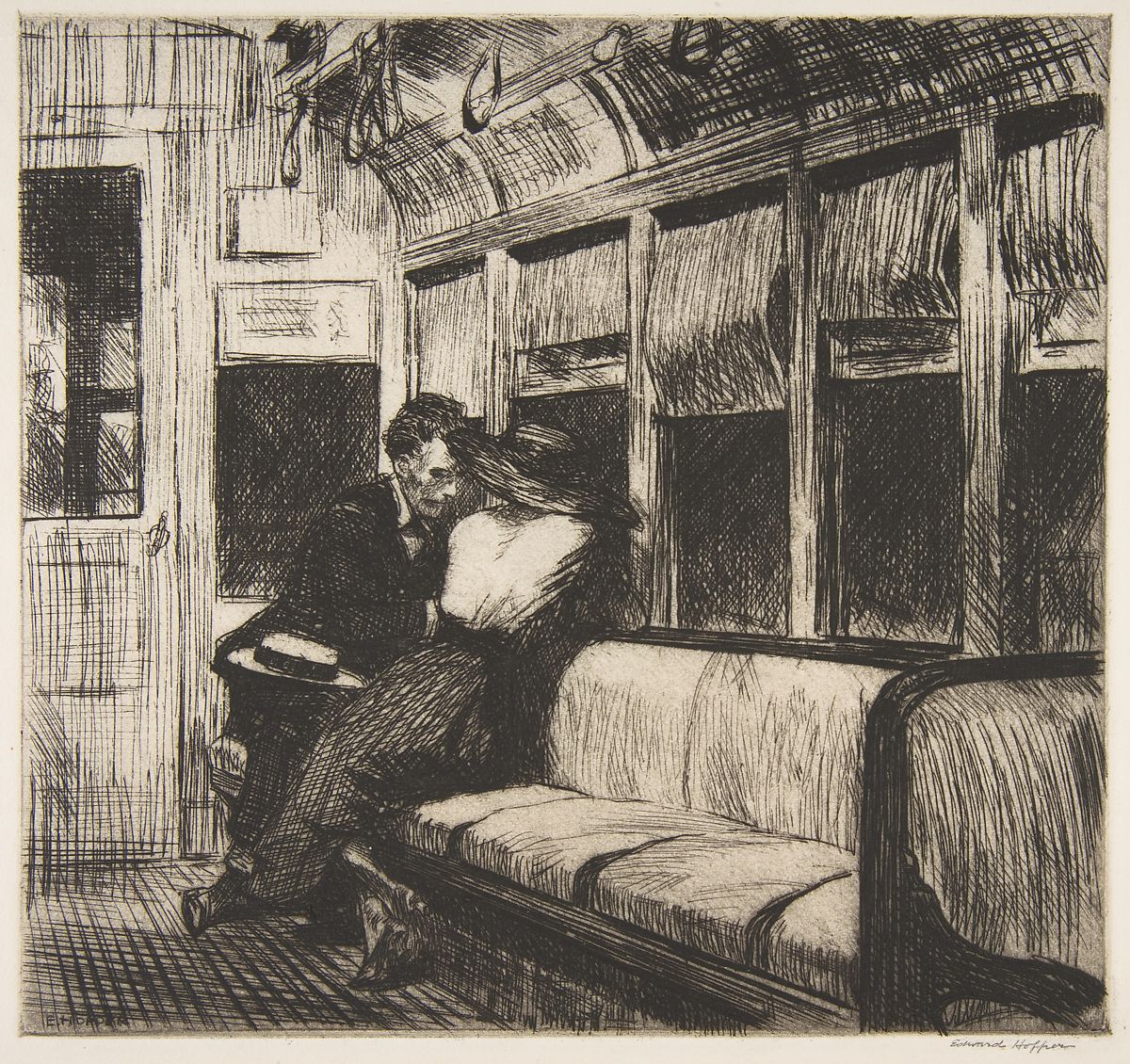

Closed interiors

House interiors, closed compartments like train coachs (Night on the El Train, Compartment C Car, Chair Car), lobbies (Hotel lobby), and rooms (Hotel by a Railroad, Hotel Window, Hotel Room) of course.

Night on the El Train, Ed. Hopper, 1918, Etching on copper, 7.5 x 8 in.

Working as an illustrator, Edward Hopper himself took the El Train back to his house. Paintings like “Night Windows” among many others certainly seem inspired by his observations from the train’s window. In this etching, he represents the pain and loneliness experienced by a big city dweller.

Architecture

House by the railroad, Room for Tourists, 1945. Cold Storage Plant, 1933, Lighthouse Hill, 1927 and City Roofs, 1932.

City Roofs, Ed. Hopper, 1932, Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 in. House by the Railroad, Ed. Hopper, 1925, Oil on canvas, 24 x 29 in.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Levin, Gail: Edward Hooper, The art and the artist; 1980 by W. W. Norton & Company.

- Taschen, Benedikt: Edward Hooper, Tranformation of the real 1882-1967; 1990.

- Mamunes, Lenora: Edward Hooper, Encyclopedia; 2011 by McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Basil | @itbwtsh

Tech, Science, Design, Economics, Finance, and Books.

Basil blogs about complex topics in simple words.

This blog is his passion project.