Abstract

Imagine standing on a long corridor with closed doors that stretches to infinity on both ends. One keeps walking along and knocking on each door, maybe trying to pick the lock, peeping through the keyhole, or even trying to break in. But the process is tiresome and hopeless. And yet once in a while, someone manages to open a door and view a world they have never imagined. The story of scientific innovation is roughly similar to the story of the endless corridor.

In 2015, Junjiu Huang and co. at the Sun Yat-Sen university in China modified the gene responsible for beta-thalassaemia, a genetic blood disorder leading to anaemia, in non-viable embryos. Through this experiment, they had opened a new door - a door that led to a utopia of a disease-free humanity and, if I get ahead of myself, of “designer” humans and GMOs.

In this post, we’ll dive deep into CRISPR, the gene-editing tool that has taken the world by storm. The focus of this post will be on the technology rather than the social, political, or governance fallout of the tool. Previous understanding of genetics and biochemistry is recommended.

Adaptive immunity and CRISPR

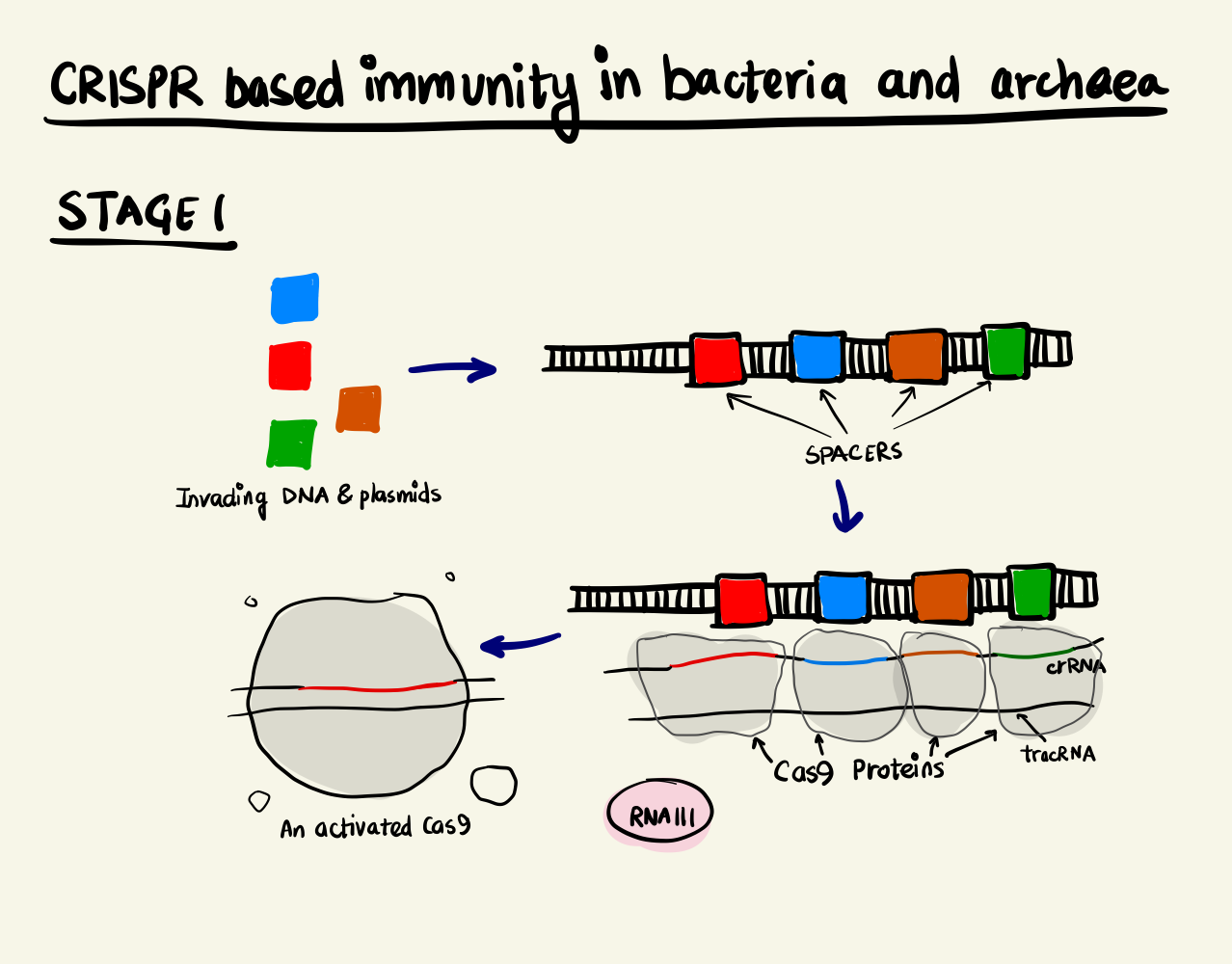

Adaptive Immunity System in bacteria and archaea, stage 1 Adaptive Immunity System in bacteria and archaea, stage 2

Biological systems are known to be highly resilient towards a changing environment and this resilience stems from their ability to adapt quickly to changing environmental parameters. Bacteria and archaea protect themselves from viruses and plasmids by an adaptive immunity system. The crux of the mechanism is based on recording the genomic fingerprint of the intruder and to deploy proteins that splice future invaders based on the “memory” that it has developed over time. Short sequences of the invader’s genome are integrated into the bacteria or archaea’s genome. These short sequences are called Clustered Regulatory Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats or CRISPR. These sequences along with CRISPR-associated proteins or Cas proteins form the machinery that enables this feature.

The CRISPR locus have two types of sequences, a highly variable region, called spacer, that constantly gets updated with new incoming invader genomic data and non-contiguous repeat sequences that separate them. Upon transcription, this stretch of DNA is expressed as a special RNA sequence called crRNA (CRISPR RNA) which doesn’t undergo translation but serves as activation director for Cas proteins. The crRNA enabled Cas9 is, then, able to bind to DNA sequences that are complementary to the crRNA and cleave them. The degradation of the foreign DNA renders the attack void and thus, immunity is gained.

CRISPR-Cas9 system: How it works

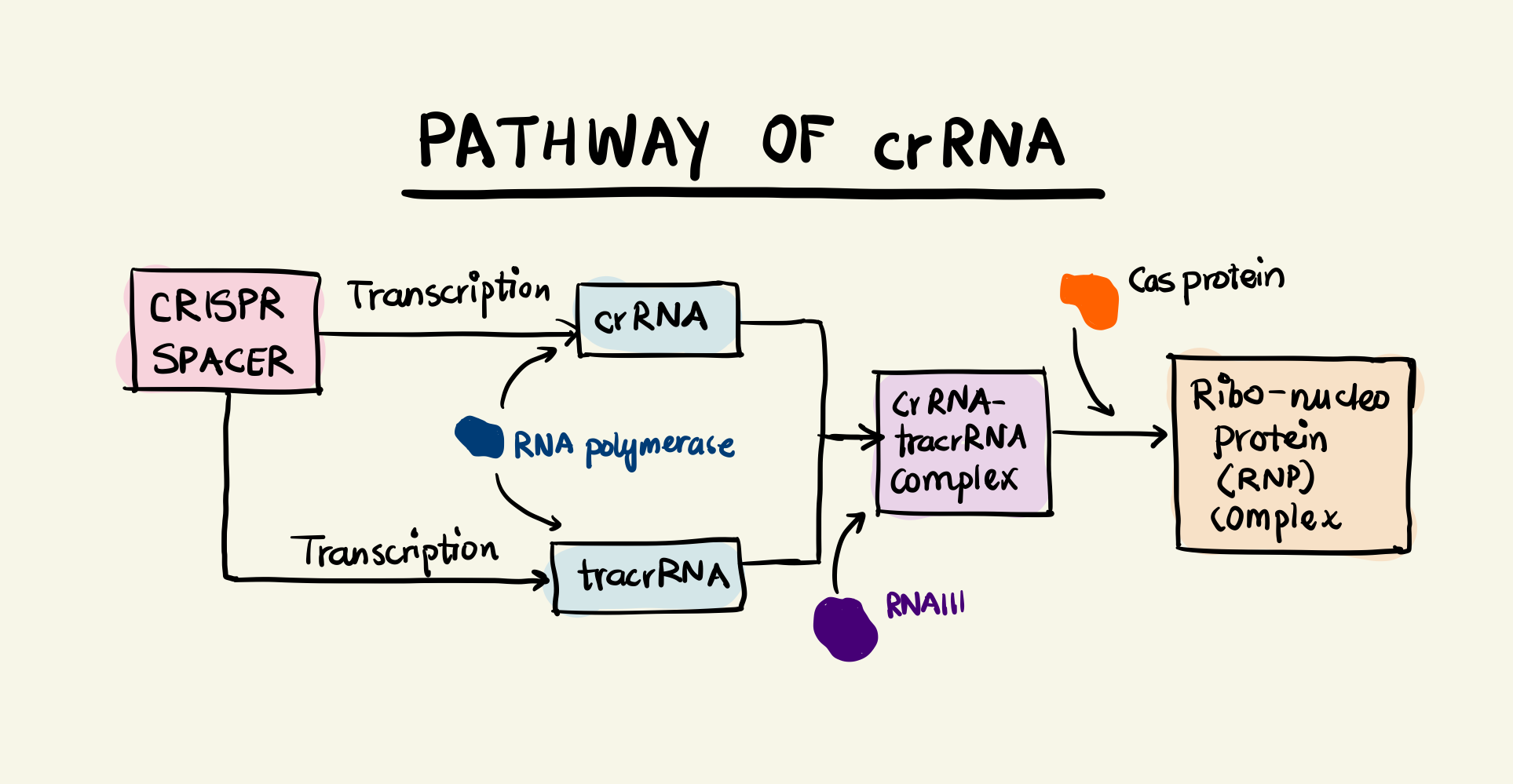

Block diagram showing the pathway of the crRNA

The interplay between CRISPR and Cas proteins that impart immunity to the bacteria/archaea. Three different types of CRISPR-Cas systems have been identified by researchers: Type I, Type II, and Type III. All systems differ in their exact mechanism to generate crRNA and Cas proteins and eventually catalyse the cleavage of DNA. Our focus will be to understand Type II systems owing to their simplicity and adoption in gene-editing. It uses a single Cas protein called Cas9 and two RNA components. We have met one of these components namely crRNA. The other component is transcribed from a locus upstream of the CRISPR locus on the mother sequence. This sequence is called trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA). The tracrRNA has a region complementary to the repeat region of the CRISPR locus and thus can bind to the transcribed crRNA (I’m simplifying details here as there’s something called a pre-crRNA which undergoes epigenetic modifications). The double stranded RNA (tracrRNA and crRNA) undergoes cleavage by a RNA nuclease called RNAIII and the crRNA-tracrRNA complex binds with a Cas9 protein to form a ribonucleo-protein (RNP) complex.

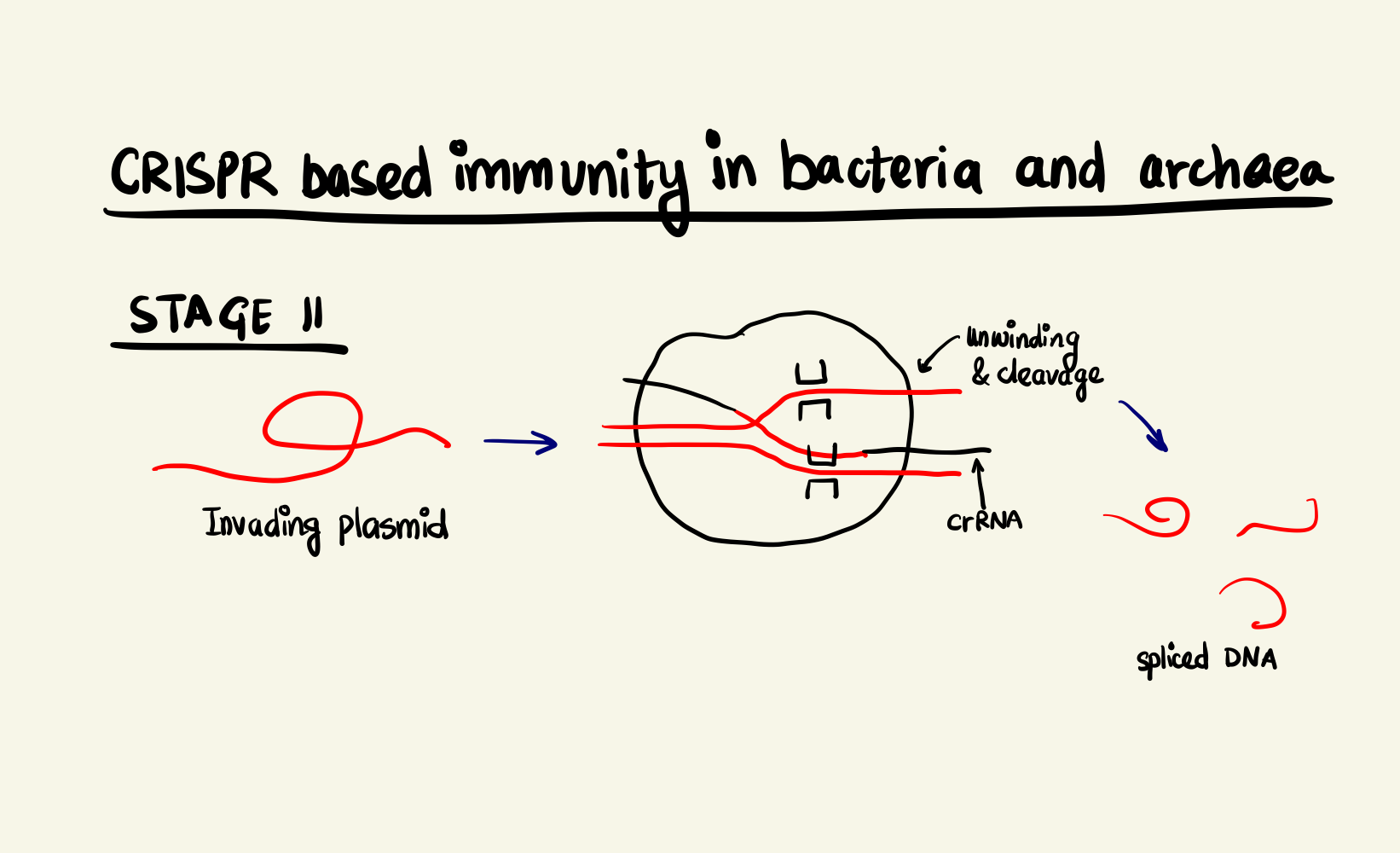

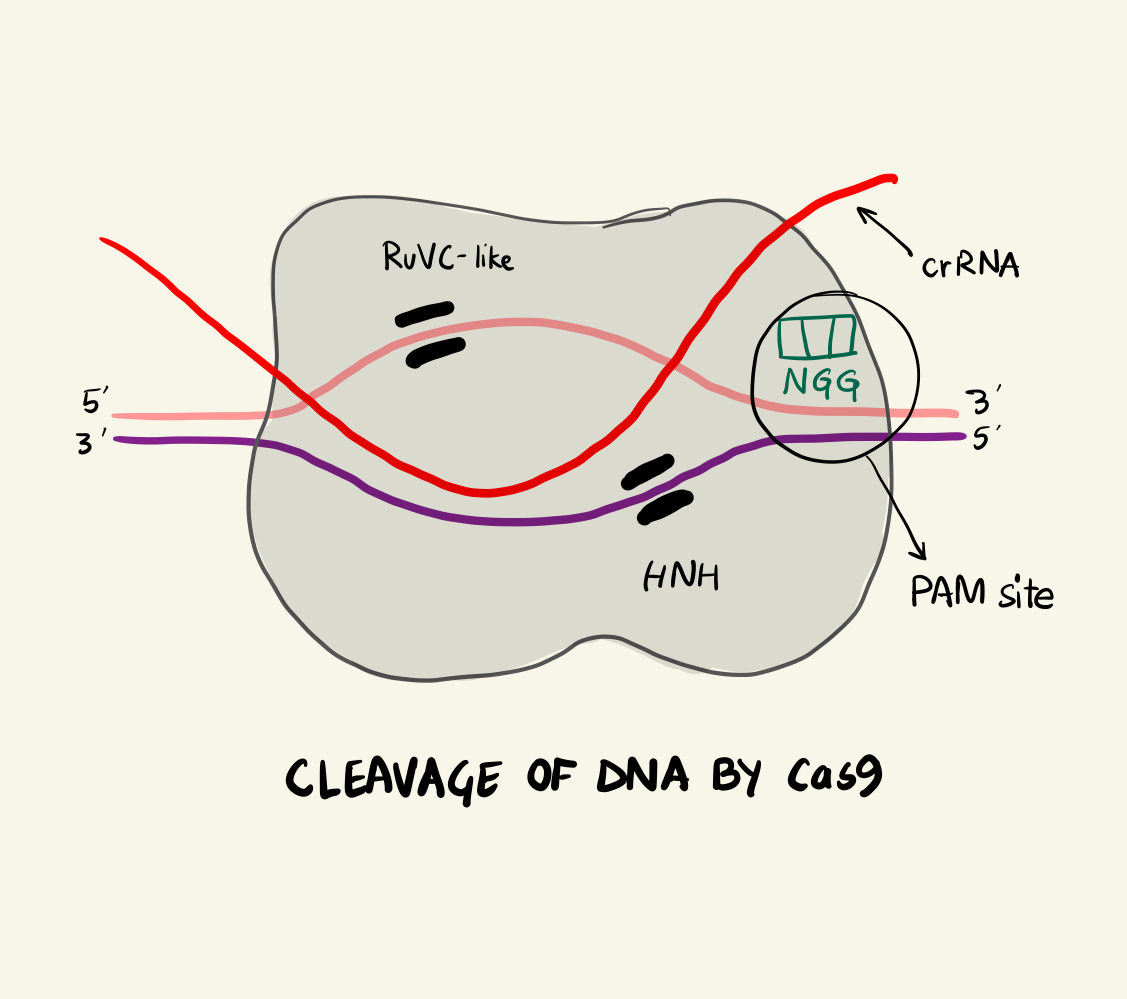

The Cas9 protein can be termed as an RNA-activated endonuclease as it can specifically cleaves DNA that are complementary to the associated crRNA strand. The Cas9 looks for spots along the invading DNA sequence after binding to regions on the invading plasmid DNA called a Proto-spacer Adjacent Motif or PAMs. There are different PAM sites associated with different Cas9 proteins. For example: S. pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) recognises a 5’-NGG-3’ PAM site and it is most commonly used for gene editing. Finding different Cas9 proteins to attach to different PAM sites gives the geneticist a versatile toolkit and increases the efficiency of the editing but we’ll get to that later.

In the case of SpCas9, two arginine residues bind to the guanine nucleobase on the PAM site (the two GG from NGG and N could be any nucleotide base). This interaction positions the phosphate of the DNA backbone to a phosphate-lock loop on the Cas9 and facilitates DNA unwinding. After unwinding, the crRNA forms a RNA-DNA hybrid called an R loop and then cleavage occurs. There are two domains on the Cas9 namely: HNH and RuvC-like. They individually nick one strand of the DNA resulting in a double strand break. The HNH nicks the strand complementary to the crRNA and RuvC-like nicks the other strand. This cleavage happens 3 base pairs (bp) upstream of the PAM site in case of SpCas9. As the cleavage is successful, the invading DNA is rendered harmless as it cannot be expressed effectively anymore.

DNA repairs and motivation for editing

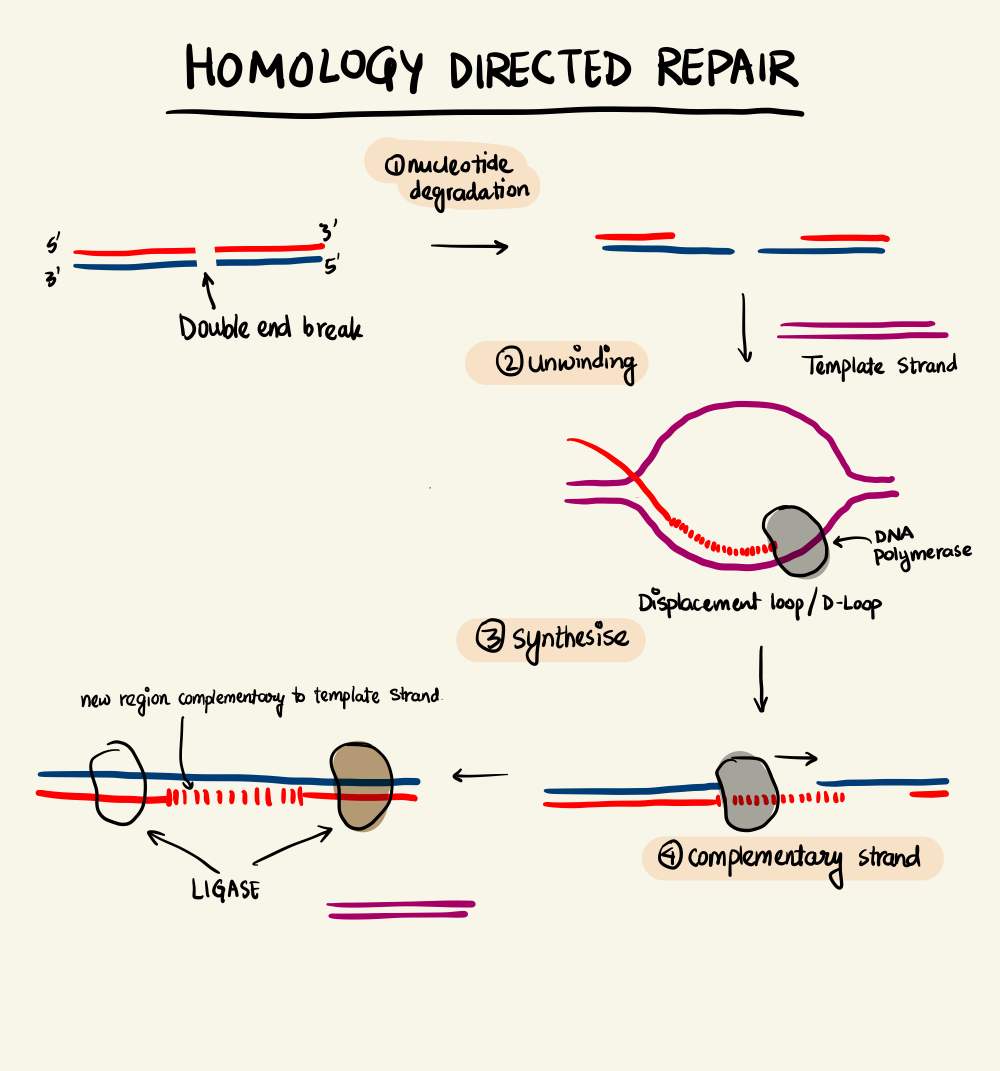

Homology-Directed Repair

DNA-RNA systems are highly versatile and robust. In response to a Cas9-induced double break, the organism employs machinery to repair the DNA. There are two types of DNA repair - Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). NHEJ can be either canonical NHEJ (c-NHEJ) where the two ends are simply “glued” back together or alternative NHEJ (alt-NHEJ) where each strand is cut out to repair the damage. Both these pathways are highly error-prone resulting in unintentional insertions and deletions.

On the other hand, if there is a complementary DNA strand nearby the double break, the homologous DNA can easily bind to repair the break. This is the Homology-Directed Repair pathway. HDR is exploited to introduce engineered sequences into the genome by making the edited strand available near a double break. Thus, to edit a gene, we need to make a cleavage at the desired location which is achieved by the CRISPR-Cas9 duo by making sure the crRNA is transcribed and RNP complex is formed. Further, we check for the availability of a PAM site near the point of interest and finally, to make sure that the engineered strand is available during repair.

A lot of research and study has gone (and is still going) into the role and importance of the various machinery involved in gene editing. The tracrRNA seems to be important for DNA cleavage by Cas9. Additionally, instead of introducing separate tracrRNA and crRNA, researchers can introduce a single guide RNA or sgRNA. This reduces the number of components involved and makes the process simpler.

Steps of a gene edit

Let us investigate the steps needed for an edit in greater detail. The process can be divided into roughly three steps:

- The selection of a suitable target and guide.

- Introduction of CRISPR-Cas9 and template DNA components into the organism.

- Identification of the mutation.

Target Selection

In the case of SpCas9, there is a 20-nucleotide sequence of guide RNA adjacent to the PAM site, 5’-NGG-3’. For best results, the PAM site should be as close as possible to the mutation locus. In fact, the efficiency for a mutation is inversely correlated to the number of base pairs from a PAM site. This is important because if the specificity of the target is not sufficient then the Cas9 can bind to other off-target regions and splice at unintentional locus resulting in edits that we don’t want. Factors that affect RNA efficiency is an active area of research in CRISPR research today. For example: the presence of purine bases (G or A) at the 3’ end of the 20-nucleotide guide is known to increase efficiency.

Introduction of different components

Cleavage of DNA by Cas9

There are primarily three forms in which we can introduce the components:

DNA form

In this pathway, we have to introduce the DNA sequences for sgRNA and Cas9 protein. The point being that we wholly rely on the translation and transcription facilities of the cell for the production of Cas9 protein and sgRNA. Now, as the Cas9 DNA is transcribed into its complementary mRNA, the presence of appropriate 3’ and 5’ untranslated regions (UTR) is ensured for successful translation into the protein. Lastly, a promoter must also be present upstream of the transcription site to bind a RNA polymerase. A promoter must also be present for the transcription of the sgRNA sequence by RNA polymerase III, which is a polymerase which specialises in the expression of ribosomal RNAs and tRNAs. Note that the ultimate product of the sgRNA pathway is RNA and not protein.

RNA

Instead of depending wholly on the cell to produce the required components for an edit, we can ease the burden by synthesising few components outside the cellular system. In this pathway, we introduce sgRNA and mRNA encoding Cas9 instead of DNAs for the same. However, the mRNA needs to be modified post transcription with a 5’ cap and a 3’ poly-A tail.

RNP/Protein complexes

Following the same theme, we can synthesise Cas9 itself and introduce the Cas9 complexed with tracrRNA and crRNA as the RNP complex entity. This pathway is ideal if we do not have the requirement to optimise for the species-specific UTRs and promoters. However, the purification of the protein and complexing in-vitro increases the cost of introduction of the components.

Identification of the genetic mutation

The efficacy of gene editing can only be determined if we are able to identify the desired mutation in the target genome. Identification of genetic modification is a significant bottleneck in the modern CRISPR workflow. There are two types of methods:

- Screening

- Selection

Screening

In screening for a specific phenotype, one can screen for the corresponding molecular change as a result of the edit. One particular assay is called restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP) analysis. The idea being that the region of interest after a mutation is amplified by PCR and then treated with a restriction endonuclease which cuts a specific DNA sequence. If the enzyme is able to cut, then we still have the unmutated sequence and there is no edit and vice-versa. The DNA fragments can easily be visualised by gel electrophoresis.

However, one disadvantage is that the mutation itself can create another restriction site. There are other endonuclease-based assays such as CEL1 and bacterial T7 endonuclease that recognise and cleave single bases. They have the advantage that they do not rely on creation or destruction of restriction sites. But this process requires a large number of candidates and is thus time consuming.

Selection

Selection relies on the fact that lethal template DNA would kill the cells but the ones with the mutation will not be killed. So, a drug-resistant edit is achieved in the cells with a successful splice whereas other cells are killed by the introduction of the HDR template strand.

Variations of the core CRISPR-Cas9 model

Expression of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) in lab mice

In this section, let us look at other exciting applications of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. The CRISPR gene editing technique derives its utility from the specificity of the Cas9 incision. Now, we can increase the specificity of a particular cut by randomly deactivating one of the domains of the Cas9 protein. In this case, Cas9 proteins are only capable of nicking one strand on their own and it would require two Cas9 proteins to make a double strand break. This increases specificity and protects against unintentional splicing.

Another point of interest is the PAM site and its essential presence for the Cas9 to bind. Researchers are looking at other proteins that bind to different regions - one such candidate is Cpf1, which recognises T-rich PAM sites and cuts at a 5’ overhang resulting in a protruding ragged end. This increases the robustness of the process as biologists can now target AT rich sites as well.

Specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 systems allows gene editing to be successful but the splicing is only the second step of the process of correctly identifying a sequence of interest. If we can deactivate the Cas9 proteins (called dCas9 in the business), and load a custom domain on the Cas9 then we can achieve more varied operations at a particular locus of interest. It’s like having an operating table running along the DNA strand. For example, if we fuse the dCas9 with a domain that represses transcription then we effectively silence the expression of the targeted genes. If the payload is a promoter, then we can activate transcription at the targeted site. We can introduce epigenetics modifiers such as methylators or histone modifying enzymes, all of which modulate transcription at the target site. A fluorescent protein called Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), derived from jellyfish, has been attached as payload to the dCas9 and used to visualise target genomic sequences complementary to the sgRNA.

Conclusion and ethical concerns

We have certainly come a long way from where we started. If I have been able to even give you a gist of what CRISPR is, then I consider this post a success. All errors and bad explanations are my fault. We began this post with the chronicle of the Chinese scientists who eliminated beta-thalassaemia from non-viable human embryos. Under very close regulation, another research group edited heterozygous embryos for a mutation in the MYBPC3 gene using CRISPR. This mutation resulted in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which can cause sudden death.

We have unlocked a truly novel technology, one that allows us to reach out and rewrite who we are but at the same time, we are also accountable for what we do. I guess that is the price we pay for knowledge.

References and Acknowledgements

- Molecular Biology at the Cutting Edge: A Review of CRISPR/Cas9 Gene editing for undergraduates - Thurtle, Schmidt, Lo, et. al.

- GCR Biosecurity curriculum: Biosecurity Fundamentals

- Homology-Directed Repair animation video - Oxford Academics on YouTube

Basil | @itbwtsh

Tech, Science, Design, Economics, Finance, and Books.

Basil blogs about complex topics in simple words.

This blog is his passion project.