It is human tendency to become unconditionally enchanted by something popular regardless of its intrinsic value. Known by many names like network effect, herd mentality, etc., this psychological effect has a diabolic effect on information dissemination. This is especially true when there is high variance in the educational distribution of the population. Take the room temperature semi-conductor craze for example. Or the plethora of medical news during the 2020 pandemic. Or the invention of the web. You get the point. It’s everywhere.

Something similar has happened to the blockchain technology, made popular by a 2008 anonymous paper. The real information about the tech and its implication is so sparse and shrouded in so much nonsense that the market around it has emerged as a scam/fraud leading to less credibility and trust.

In this post, I wish to discuss how blockchain tech may not be the panacea of decentralised commerce as it has been once been marketed as. I will discuss design flaws inherent in the Ethereum chain and what it means for the properties that enabled Ethereum to differentiate itself from traditional financial systems.

Note: This post assumes the older Ethereum consensus mechanism, namely Proof-Of-Work.

Frontrunning

Front-running (noun): The practice by market-makers of dealing on advance information provided by their brokers and investment analysts, before their clients have been given the information.

Let us take an example. Imagine there are two parties Alice and Bob. Alice somehow gets to know that Bob is about to make a “big” trade, that is, he’s about to purchase a lot of cookies. So, just before Bob’s purchase order, Alice goes to the market and buys a lot of cookies for herself thereby raising the price of cookies. Now, as Bob’s purchase order is processed, he has to pay more money for the same commodity. Alice has managed to extract money from Bob simply by knowing about Bob’s purchase order in advance. Note that there’s also a bunch of other factors, most importantly the design of the trading platform that Alice and Bob are using that affects how big this problem can be. In some ways, frontrunning is a fundamental design flaw in the very act of trading.

Traditional (that is, centralised) financial trading firms use a purchase order book to match up buy and sell orders. If Eve had access to this list of buy and sell orders, she would be able to anticipate the price changes that some of those orders would have and frontrun those transactions to make money out of thin air. Frontrunning is illegal on CeFis and govermental agencies oversee that brokers and trading agencies don’t engage in such activites.

Exploitable opportunities

What kind of purchases can lead to frontrunnable opportunities? Large volume orders are an obvious example. A buy order of 0.5% of all tradable ETH would have a substantial impact on the price of ETH. It would also create arbitrage opportunities across multiple markets that would decay based on the oracle latency between them. Even human errors in placing buy and sell orders can lead to frontrunnable scenarios in DeFi as we’ll see later.

Unlike CeFi, DeFi are designed to be transparent, that is, transactions are public. One cannot be decentralised if one cannot see what’s going on…which makes sense. But now, let us understand how this design feature aggravates frontrunning on blockchain and reduces consensus security.

In the Ethereum protocol, local transactions are broadcasted via a gossip protocol to nearby nodes and are processed by rational miners based on the decreasing order of transaction fees. However, there is always a publicly accessible set of unconfirmed transactions called a mempool. It contains transactions that might potentially fail or be valid but nobody knows. As you can imagine, this presents perfect oppurtunity to frontrunners who can examine the mempool and frontrun profitable transactions without a fuss.

An example

Most DeFi exchanges are based on the purchase orderbook mechanism in which a centralised clearing house matches a list of buy orders with a list of sell orders when they find compatible trades. In a DeFi, the central authority is, of course, the immutable logic of the smart contract behind the exchange. Note that this is a different design than the more innovative automated market maker model introduced by Uniswap. Now, let us see how a frontrunning transaction can exploit an erroneous trade order.

Let’s assume that someone offers to buy an asset at 10x the market rate (perhaps due to a slip while filling the price or a decimal point error). A bot would identify this opportunity and quickly buy that asset from the market and then sell this back to the original buyer. This is possible because of the inherent atomicity of transactions on the blockchain via so-called blocks. Moreover, the incentive mechanism for miners to “mine” a particular trade is assumed to be strictly dependent on the transaction fee they reap out of the order. Hence, in order to prioritise a transaction, one only has to set a marginally higher transaction fee to frontrun a transaction. We’ll see how this leads to an interesting phenomenon.

On the flip side, let us assume that someone offers to sell their token at .1x the market rate (again, an error). A frontrunner might buy those token immediately and sell them in the market and gain 0.9x profit.

Arbitrage and frontrunning situations can arise from a number of factors such as price difference of the same asset across markets and the different response rates for market movements based on platform design, logic bugs, human error, etc. Generalising this, a sophisticated frontrunning bot will replay a number of shortlisted transactions in the mempool in a local environment and try to frontrun one or a sequence which leads to a net positive profit for itself. The exact profit is difficult to calculate simply because it is not possible to anticipate the subset of transactions visible to a bot which depends on a number of factors such as latency, network congestion, and the well-connectedness of the bot.

What I described above is a particular type of exploiting frontrunnable transactions dubbed “pure revenue opportunities” by this paper. Due to the unique public nature of these transactions, a victim can see what happened with their funds. I reproduce few comments made by victims of such bots from the paper linked above.

“I am a single parent trying to make ends meet at a job I hate. Please have some mercy.”

“Please I ask you to send me the ETH back as I really need it to continue my education. I might need to sell my car to pay what is already due for this semester.”

“This was obviously a mistake transaction - any chance you can find it in your heart to send it back?”

Priority Gas Auctions (PGAs)

The mechanism for exploiting an abitrage opportunity is by placing your order before the victim order. In the blockchain paradigm, this translates to assigning a higher transaction fee to your transaction to incentivise a rational miner to include the attack transaction first. But an interesting phenomenon happens if two bots find an exploitable transaction. In this case, a naive strategy bot A would keep increasing their transaction fee in response to bot B, following the same strategy, and trying to nullify A’s attempt to reap a profit. This leads to interesting series of transactions with the same nounce but incrementally higher gas fee by two wallets for the same trade - a pretty conspicuous phenomenon.

Due to the stochastic nature of block inclusion time (which depends on the miner being able to find a solution to a cryptographically hard problem), the transaction to be actually included is not pre-determined.

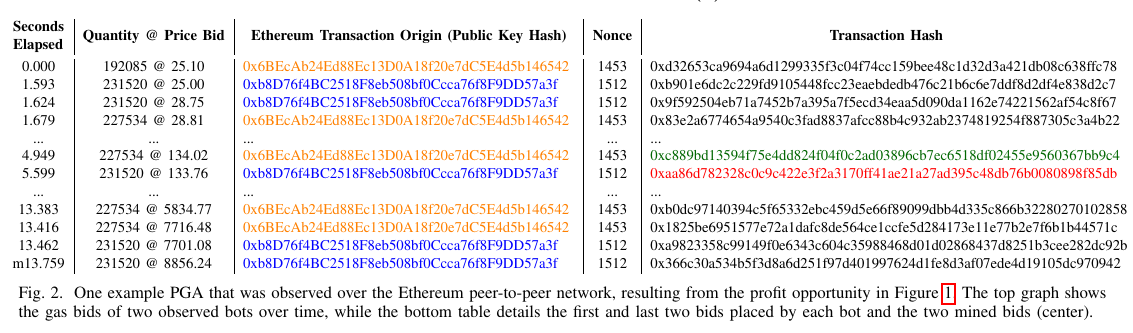

Source: Flash Boys 2.0

Note this interesting PGA battle where two bots engaged in a biding war. Eventually, the green transaction for 0x6BEcA... was included at 134.02. Interestingly, the bots agreed to raise their fee to ~8K. The other transactions were, of course, discarded from the mempool once the winning transaction was mined.

Bots can adopt different strategies for bidding in such auctions. Two of the simplest and observed strategies are:

Blind raising: Simply increase the bid by a fraction until the order is successful. This is a non-adaptive strategy and doesn’t take into account what the other agent is upto.

Counterbidding: As the name suggests, only raise the bid if the current bid will lead to failure and raise the bid by a certain fraction of the other agent’s bid.1

Moreover, the winner of a bid war is highly dependent on the latency of the network and the connectedness of the bots to the network, hinting at the development of high-frequency trading-like scenarios on blockchain platforms; an undesirable and unintended consequence of the current design of the system.

Transaction reordering and unintended optimisation

Once in the mempool, the miners have a lot of freedom in choosing which transactions to include in the block they’ll mine next. The protocol assumes that rational miners would order transactions by decreasing transaction fee which is the intended behaviour. However, if the miners have a greater incentive from outside the system to deviate from this behaviour then it leads to lowered network security. Studies show that at certain thresholds, miners are incentivised to even fork the chain.

If a miner is aware of a transaction sequence that would lead to profitable outcome or even personal connections with the transaction participants, they can reorder transaction orders if the profit from such reordering is greater than the transaction fee. When can such scenarios occur? Once large volume trades are detected in the mempool, miners may identify potential frontrunnable transactions or more sophisticated types called “sandwich attacks” (flank the victim transaction with two attacking transactions to bet in favour of a condition that is determined to occur as an outcome of the victim transaction). Miners can collude with third-party users and reorder transactions to maximise the block reward they can mine. They may also censor transactions of a particular kind, type, demographic, and so on. One quickly realises how this design pattern can fundamentally compromise blockchain security.

Conclusion

While transacting on the application layer, it is often possible that endusers abstract away the complexity of what goes under the hood on the Ethereum protocol which enables them decentralised consensus. But we find that the mempool is not a utopic panacea that will enable blockchain to replace traditional CeFi. This primarily arises from fundamental design flaws that were not originally conceived - an ideal case study to understand why engineering is hard.

I haven’t even scratched the surface of how profitable these “extractable values” have been for adversaries in the past (for numbers, check out the Flash Boys paper) and still continue to be a source of income for sophisticated bots. The original paper Flash Boys 2.0 dubbed this value as MEV or Miner Extractable Value but after the transition to PoS, it was proposed to name it as Maximum Extractable Value. This paper argues that MEV is a subset of total extractable value which it dubs BEV or Blockchain Extractable Value. So, even if the terminologies are not very definite, I hope the problem is.

Well, the above picture might seem more grim than the situation is. Currently there is amazing work going on which will nullify wealth stealing by transferring the incentives to the users and miners. An interesting middle layer is being built - for example, MEV Boost for PoS-enabled blockchains.

References

- paper Flash Boys 2.0: Frontrunning, Transaction Reordering, and Consensus Instability in Decentralized Exchanges: Daian P. et. al

- paper Quantifying Blockchain Extractable Value: How dark is the forest?: Qin K. et. al

1: I am simplifying a lot of details here. For example, transaction fee increments are not continuous. Most ETH clients require a bid to be atleast 12.5% of the initial bid to be considered for inclusion thus making bidding discrete in practise.

Basil | @itbwtsh

Tech, Science, Design, Economics, Finance, and Books.

Basil blogs about complex topics in simple words.

This blog is his passion project.