Introduction

Art, by its very nature, challenges the status quo. It has the power, and I would argue, responsibility, to sway people to stand up against unjust and authoritarian regimes. It serves as the voice of the marginalised and the voiceless. The twentieth century philosopher Theodore Adorno famously said,

“All art is an uncommitted crime”.

~Theodore Adorno

The acclaimed Spanish painter, Pablo Picasso painted The Guernica as an expression of protest against war. Its explicit and ghastly imagery has been used in anti-war protests ever since. Or, take contemporary artist Banksy’s protest poster for Black Lives Matter which shows an American flag catching a fire by a vigil candle beside a framed photograph of an unknown person.

Paradoxically, the imaginatively free artist is a prisoner of their era. Their protest must be subtle, but potent for it must awaken the oppressed without awakening the oppressors. But to achieve this adroit mode of expression is a challenging task. The 1960s saw the French cinematic landscape waking up to an obtuse and blatant attack on their culture by the Americans — a cultural attack. In such a state of jeopardy, the burden fell on a group of young French film-makers to define a truly French style of making films.

Jean Luc-Godard, along with Truffant and Resnais pioneered this task and gifted the world, a new form of film-making; one completely detached from American roots and in glaring defiance of the conventional “acceptable” ways of filmmaking. Breathless (À bout de souffle) was Godard’s debut feature length film that took the world by storm and together with Truffant’s The 400 Blows and Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour ushered what was to be christened the so-called “French New Wave”.

Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960)

If you watch Breathless for the first time, chances are that you will find it rather uninteresting. And yet, it is perplexing how it manages to end up on almost all influential “Top X movies list”. So, what’s the big deal about it, anyway? Just like a tourist whose appreciation for a monument is diminished because of a lack of sound grounding in the context, culture, and history of the place, it is difficult to convey what Breathless really stands for, if viewed superficially. This post is my attempt to note some and hopefully make my reader appreciate this genius tour de force.

Breathless was less of a movie and more of a symbol of protest. A rebuttal. A counter-attack. But to understand its significance is to first understand the time in which it appeared.

What was the French New Wave? What started it?

In 1946, an agreement was signed between American Secretary of State, James F. Brynes and Leon Blum, a representative for the French government, to wipe away France’s war debt by opening American markets to French consumers after France’s liberation from Nazi control. This agreement was called the Blum-Brynes Accords and it shaped the French culture at an astounding rate. This event triggered a chain of interesting events, the ushering in of the French New Wave movement being one of them.

By 1948, barely two years after the Blum-Brynes Accords, 222 American films populated French cinemas. This shocked French fimmakers because a meagre 89 French films were released that year and only 8 from other countries. The American economic upperhand was posing a serious threat to the identity and existence of French cinema and in turn, French culture. It was a wake-up call for French filmmakers, a call-to-action, if you will.

In such a setting, comes Breathless out of Godard’s mind, a product of envy after his friend Francois Truffaut won big at Cannes for “The 400 Blows”. It incorporated styles and techniques that were outrightly considered as “unsuited” for any kind of filmmaking by American directors. Crowther, a Times critic remarked of it, “sordid is really a mild word for its pile-up of gross indecencies.” And the infamous jump cuts to him were “pictorial cacophony.”

Plot

The plot is the classic noir staple of the 50s. A petty thief, Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) who is on the run for murdering a police officer and the subsequent chase through the streets of Paris, all the while accompanied by his American girlfriend Patricia Franchini (Jean Seaberg). But this is where Breathless stops being any other noir film.

The Politics of Breathless

If we were to analyse characters in Breathless, it would be a relatively easy task. And yet one character would prove to be a real difficulty. Patricia. Indeed, it is Patricia and her relationship to Michel that provides dynamics to the main plot.

Who is Patricia? She doesn’t get shocked when she learns Michel is a murderer, rather helps him get away. She responds to the fact that she might be pregnant and Michel might be the father with an urgency that is unsettlingly lacking. Like a side conversation that slipped off. She smirks in a mysterious fashion when a writer at a lunch meeting talks about how he was about to bed a girl but missed it. She doesn’t protest Michel’s marriage status when she learns about it or even deters him from blatant eve-teasing on the streets. Patricia justifies her betrayal as a test of whether she loves Michel or not; a personal exercise, and not as a moral obligation. It is very difficult to imagine what she is thinking behind that pretty face. She is the central enigma of Breathless.

Scene with the colleague.

The character of Patricia can be understood through a political lens. At the climax, Patricia watches as Michel is gunned down. Patricia violates Michel’s love in the same way that Hollywood, with the help of the American government, violated French theaters. This came at a time when France was reeling from war debts and had to open its markets to American goods. It was obvious that France had an exploitative amicable bond with America. Godard cleverly disguised his personal political apprehensions in his art form so as not to “displease” his American counterparts.

For how then can one justify the fact that Michel idolizes Humphrey Bogart, an American actor and impersonates him throughout, complete with a dangling cigarette? There is a shot in the film where Michel stands directly below a large poster of Bogart for his film “The Harder They Fall (1956)”. The unnatural proportions of this shot are intentional; it is Godard teaching the budding filmmakers that to emulate the American lifestyle is to give in to an unoriginal and identity-less one. The French protagonist must stop mimicking and idolizing American actors and cultivate an identity of their own.

The crime noir plot itself, sits rather uncomfortably in the delicate streets of Paris; like a piece out of place. It was Godard’s idea of a fast-paced, car-chasing, glass-shattering thriller through the city of amour. Viewed through this prism then, Breathless is a parody of all classic American noir films made because Paris isn’t a noir location (or so we thought).

Godard intentionally breaks the pace of the film multiple times and we are immediately reminded of that 15-20 minute single-scene conversation between Michel and Patricia in Patricia’s room. A private conversation of a couple sharing their most intimate thoughts, the state of their relationship, kissing, having sex, casually smoking, laughing. Who would expect that in a “fast-paced, car-chasing, glass-shattering thriller”?

This is the cinematic equivalent of Galileo standing before the Inquisition and mumbling Eppur si muove, slapping his oppressors on their faces while they are unaware of it, all along.

Production

Almost a written rule, a film seldom ends up being what it was originally conceived as. The same is the case with Breathless.

“I realized that [Breathless] was not at all what I thought. I thought I had made a realistic film like Richard Quine’s Pushover, but it wasn’t that at all.

~Jean-Luc Godard

Godard debuted with Breathless and thus, didn’t have enough credibility to enjoy a full-fledged crew or even decent equipment. Breathless was shot with minimal equipment and a sparse crew. Godard was lucky to have Raoul Coutard, the cinematographer on his side, who provided various ingenious out-of-the-box solutions to the shooting. For example; he took a camera and rode on a wheelchair for a tracking shot because they couldn’t afford tracks. There is a beautiful medium full shot of Seaberg’s back as she walks through the Elysee-Champs peddling the NY Herald Tribune. Coutard preferred to maneuver the camera with hands although they were heavy. Breathless wanted to give us a feel of events and the French life unfolding naturally before our eyes. Godard breaks the fourth wall often and you might recall Patricia staring directly at the audience, mimicking that Bogart move and asking, “What does he mean, “want to puke”?”

Jump Cuts

It is customary (almost tradition) to talk of so-called “jump cuts” when one talks of Breathless. But as the Australian critic Jonathan Dawson puts it,

[The technique]… was a little more accidental than political.

~Jonathan Dawson, Australian critic

Godard wanted to reduce the runtime of the final footage and went ahead with a scissor, cutting anything that he found boring. This created an interesting motif; a glitch in the matrix. As Brunch laid down in his phenomenal essay, “In the Blink of an Eye”, a cut should represent either of the two motives:

- Represent a motion within a context.

- Represent a discernable shift in space, time or both.

The great (and obnoxious) thing about Godardian jump-cuts are that they sit somewhere in the middle of these two spectrums. Disorienting and unsettling, they represent the French filmmakers ready to throw away the American “rules” of filmmaking.

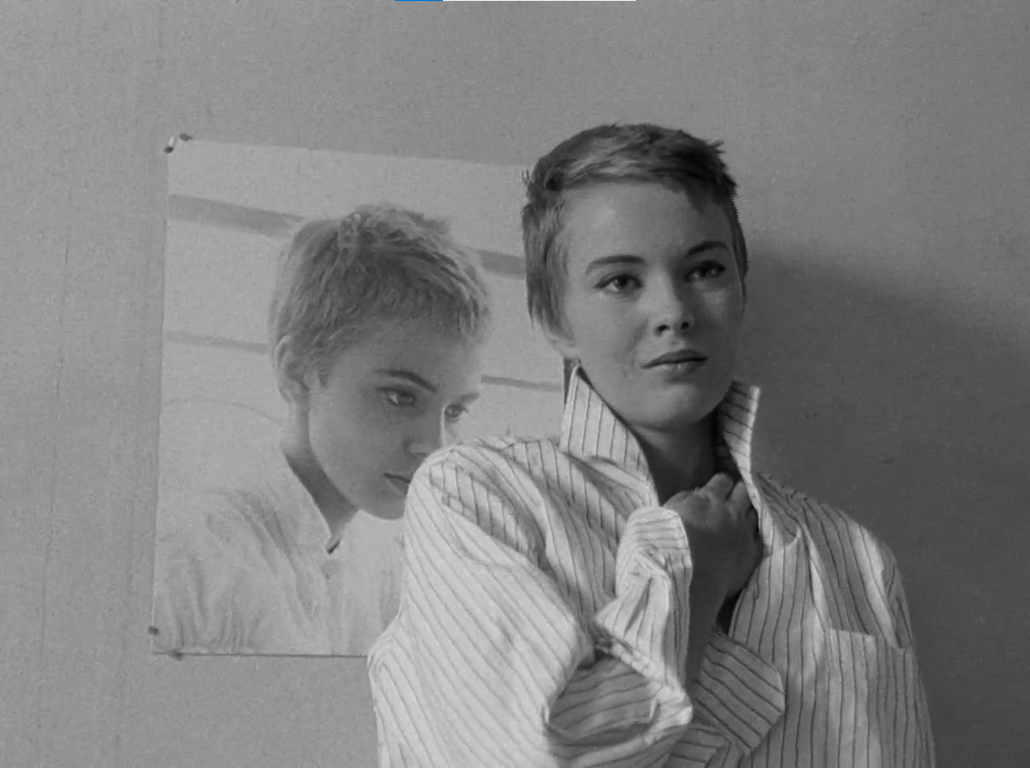

Jean Seaberg as Patricia Franchini in Breathless.

Legacy

I don’t want to bore you with a list of allocades or movie lists that features Breathless because they are only a web search away.

But imagine the transformation of the budding French filmmaker in 1960 as they walk out of the theater. A door of possibility must have opened for them, someone among them has stood up and led the way. It was, as often said before, a call-to-action. Breathless was a political statement and reinvigorated the French film culture, indeed, all of film culture as we see influences of Michel’s ragtag murderer in the likes of characters played by Pacino, Nicholson, Penn, and so on.

Even to this day, motifs from Breathless are used in contemporary movies and more explicitly, Breathless continues to be references and lives today in those films that care to notice.

Why is Breathless a work of genius?

Can a nation’s cultural identity be borrowed? Breathless is genius because in it Godard not only asks the question (or rather shows the imminent crisis to the audience) but provides a solution to that crisis in the medium itself. To break out of the American “conventional” style of filmmaking would be to emulate something like he did in Breathless, jump cuts and all. To truly cultivate an original French style of filmmaking. But Godard is walking a fine line here. To announce openly of a cultural independence from the American would be impossible. Because American economic dominance was a source of dissatisfaction for the French filmmakers as they quickly saw their livelihoods under attack by the American films flooding the French theaters.

So, what is Breathless? Breathless is an act of rebellion, a protest. It is an attempt to safeguard a nation’s culture, a political protest as much as it is avant-garde.

On the Margins

This is not a review. It’s an outpouring of my appreciation and respect rather than criticism that is known to devolve into hostility sometimmes. It is the sum of my desire to understand what’s the big deal anyway and finding something rewarding. An attempt to convey that satisfaction and a genuine solemn tribute.

A picture perfect Patricia against a Renoir.

References

- How Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless reinvented the movies - Slate.com.

- Roger Ebert’s review of Breathless - Roger Ebert

- Why French Classic Breathless is still a breath of fresh air - Scroll.in

- KultureHub’s commentary on Breathless - KultureHub

Proofread by Mahima Mukherjee.

Basil | @itbwtsh

Tech, Science, Design, Economics, Finance, and Books.

Basil blogs about complex topics in simple words.

This blog is his passion project.